India’s historical carpet weaving trade meets AI

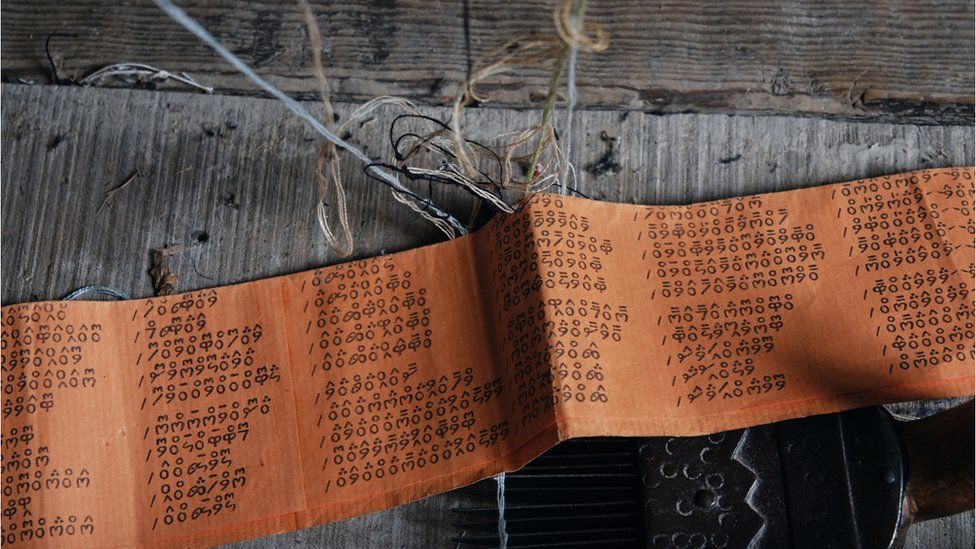

An historical symbolic code lies behind the intricate patterns of Kashmir’s conventional handwoven carpets and rugs.

Called talim, the code has been used for lots of of years to design carpets and convey data to weavers.

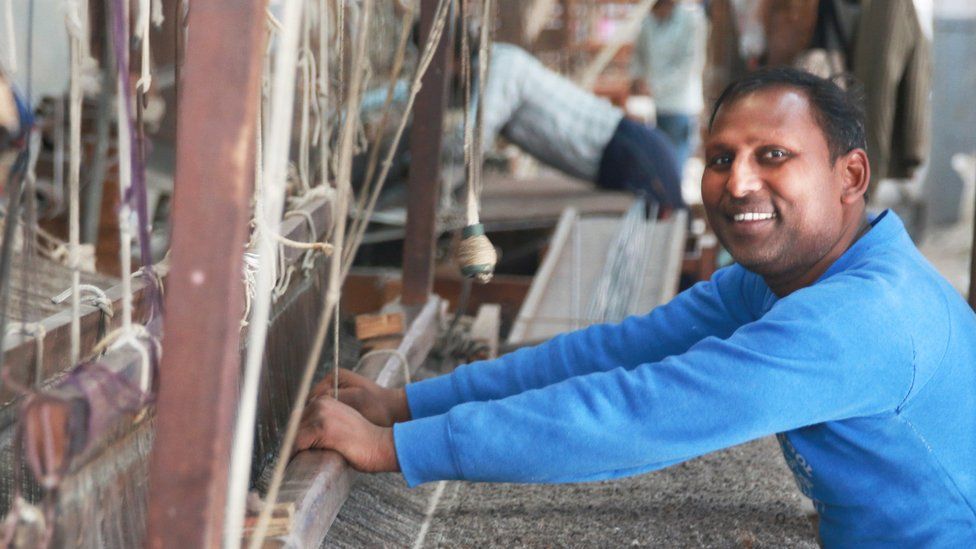

From the age of eight, and following within the footsteps of his father, Mohammad Rafiq Sofi has been weaving carpets utilizing talim designs.

“It took me five years to learn how to weave properly,” says Mr Sofi, now 57.

Much has modified throughout his half century within the trade. Mr Sofi says that within the early days it might take greater than six months to finish a carpet.

To begin the method, a designer would draw up a carpet. A talim skilled would then encode that design, and in small sections ship it off for weaving.

Those chunks of code could be translated for Mr Sofi and weavers like him, displaying them the place to knot every thread and which color to make use of.

Each part would solely symbolize a small piece of the carpet, so lots of could be wanted for the entire carpet, with a lot forwards and backwards between the designers and weavers.

The course of made errors tough to identify and time-consuming to appropriate.

But today laptop software program has streamlined the method and Mr Sofi can end a carpet in six weeks.

The weaving and knotting continues to be accomplished by hand, however now laptop software program handles the design and creation of the talim code. It means Mr Sofi can see the entire design directly, as an alternative of simply small sections.

Any potential issues may be noticed upfront, reducing down on time-consuming errors.

“This innovation in handmade carpets is not to disrupt the essence of artistic carpets, it’s just to speed up the process – designs being available now at a speed,” says Mehmood Shah, the director of Handloom & Handicrafts for the federal government of Jammu and Kashmir.

The newest innovation comes from expertise companies which can be making use of synthetic intelligence to the method.

Aby Mathew is chief working officer at International Virtual Assistance, a pc software program agency that specialises in analysing knowledge.

His firm is coaching a synthetic intelligence (AI) system to know the talim code by displaying it footage of carpets and contours of talim code.

The AI continues to be being developed and the method will nonetheless require a human to put in writing the code, however Mr Mathew says it ought to velocity up manufacturing by decoding the talim directions for the weavers.

“Weavers will be able to try out new patterns, update classic themes to suit contemporary tastes, and produce one-of-a-kind, custom carpets,” says Mr Mathew.

As India grows richer he sees an rising demand for carpets that the standard trade will battle to fulfill.

“The tastes of customers are evolving, with a growing desire for carpets that are fashionable, long-lasting, and low maintenance. Conventional carpet-making techniques are frequently labour-intensive and sluggish – they might not be able to satisfy these needs,” says Mr Mathew.

Aditya Gupta based Rug Republic 32 years in the past, it now employs round 5,000 individuals and makes as much as 15,000 rugs per 30 days. He says the Indian rug and carpet trade is dealing with stiff competitors from rivals in Turkey and China and must sustain with the newest manufacturing methods.

“Innovation is important in every industry – without it, we die,” he says.

“The Indian carpet industry is an interesting case, where it is not only about moving forward with new tech, but rather moving the old and the new hand in hand.

“The innovation now could be oriented in the direction of creating designs that can’t be copied by machines whereas nonetheless utilizing conventional methods.”

At Rug Republic, new tech has been introduced for the design, washing and drying of carpets and for monitoring moisture levels. As well as the traditional wool, materials like recycled jeans, cotton and leather have been experimented with.

Despite all the innovation, Mr Gupta still values the old methods.

“The manufacturing facet of issues nonetheless must be conventional and handmade as that’s the primary allure the customers search.”

The industry has also been helped by an official tagging system which identifies a genuine hand-knotted Kashmiri carpets.

By scanning a QR code buyers can verify the carpet designer and how it was made.

“If the [Handicrafts] division hadn’t taken this step, perhaps this commerce in handwoven carpets would have died in a number of years,” says carpet designer, Shahnawaz Ahmad.

That would have been a blow as the industry is an important part of the local economy. It employs around 50 thousand workers in Jammu and Kashmir, who collectively produce rugs and carpets worth around £36m ($28m) a year.

The developments in carpet making have given hope to old-timers like Feroz Ahmad Bhat, who has been weaving carpets for the past thirty years.

“In my early days, our earnings had been good and lots of people had been concerned with this work. Then a time got here when wages had been very low. But now new designs have been launched and this work has picked up tempo once more. Now it is flourishing once more.”