New migrants face worry and loneliness. A city on the Great Plains has a storied assist community

FORT MORGAN, Colo. — Magdalena Simon‘s only consolation after immigration officers handcuffed and led her husband away was the contents of his wallet, a few bills.

The hopes that had pushed her to trudge thousands of miles from Guatemala in 2019, her son’s small body clutched to her chest, ceded to despair and loneliness in Fort Morgan, a ranching outpost on Colorado’s jap plains, the place some locals stared at her too lengthy and the wind howls so fiercely it as soon as blew the doorways half off a lodge.

The pregnant Simon tried to masks the despair each morning when her toddlers requested, “Where’s papa?”

To thousands and thousands of migrants who’ve crossed the U.S. southern border up to now few years, stepping off greyhound buses in locations throughout America, such emotions might be fixed companions. What Simon would discover on this unassuming metropolis of slightly greater than 11,400, nonetheless, was a neighborhood that pulled her in, connecting her with authorized council, charities, faculties and shortly buddies, a novel assist community constructed by generations of immigrants.

In this small city, migrants are constructing quiet lives, removed from huge cities like New York, Chicago and Denver which have struggled to accommodate asylum-seekers and from the halls of Congress the place their futures are bandied about in negotiations.

The Fort Morgan migrant neighborhood has change into a boon for newcomers, practically all of whom arrive from perilous journeys to new challenges: pursuing asylum instances; discovering a paycheck large enough for meals, an legal professional and a roof; inserting their youngsters at school; and navigating a language barrier, all whereas dealing with the specter of deportation.

The United Nations used the neighborhood, 80 miles northeast of Denver, as a case examine for rural refugee integration after a thousand Somalis arrived to work in meatpacking vegetation within the late 2000s. In 2022, grassroots teams despatched migrants dwelling in cellular properties to Congress to inform their tales.

In the final 12 months, lots of extra migrants have arrived in Morgan County. More than 30 languages are spoken in Fort Morgan’s solely highschool, which has translators for the commonest languages and a telephone service for others. On Sundays, Spanish is heard from the pulpits of six church buildings.

The demographic shift in current many years has pressured the neighborhood to adapt: Local organizations maintain month-to-month assist teams, practice college students and adults about their rights, train others easy methods to drive, guarantee youngsters are at school and direct folks to immigration attorneys.

Simon herself now tells her story to these stepping off buses. The neighborhood can’t wave away the burdens, however they’ll make them lighter.

“It’s not like home where you have your parents and all of your family around you,” Simon tells these she meets in grocery shops and college pickup traces. “If you run into a problem, you need to find your own family.”

The work has grown amid negotiations in Washington, D.C., on a deal that might toughen asylum protocols and bolster border enforcement.

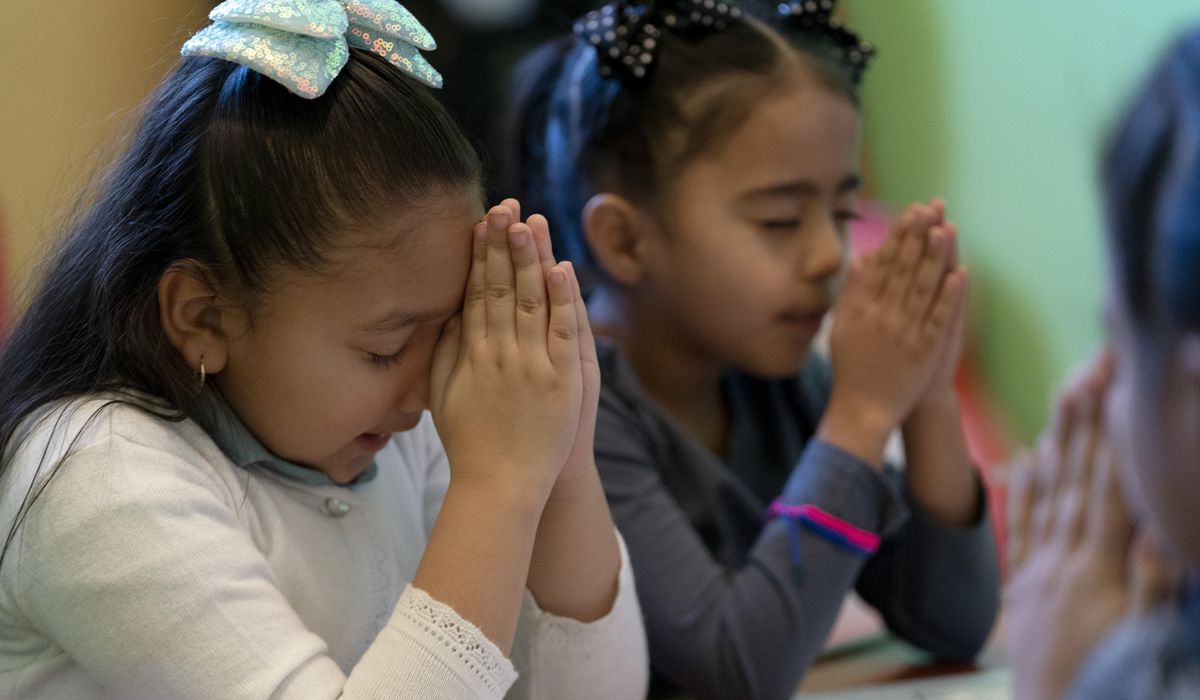

On a current Sunday, advocacy teams organized a posada, a Mexican celebration of the biblical Joseph and Mary searching for shelter for Mary to offer beginning and being turned away till they got the steady.

Before marching down the road singing a tune adaption during which migrants are searching for shelter as a substitute of Joseph and Mary, contributors signed letters urging Colorado’s two Democratic senators and Republican U.S. Rep. Ken Buck to reject stiffer asylum guidelines.

A century in the past, it was sugar beet manufacturing that introduced German and Russian migration to the realm. Now, many migrants work inside dairy vegetation.

When space companies had been raided a number of occasions within the 2000s, buddies disappeared in a single day, seats sat empty in faculties and gaps opened on manufacturing facility traces.

“That really changed the the understanding of how deeply embedded migrants are in community,” mentioned Jennifer Piper of American Friends Service Committee, which organized the posada celebration.

Guadalupe “Lupe” Lopez Chavez, who arrived within the U.S. alone in 1998 from Guatemala at age 16, spends lengthy hours working with migrants, together with serving to join Simon to a lawyer after her husband was detained.

One current Saturday, Lopez Chavez sat within the low-ceilinged workplace of One Morgan County, an almost 20-year-old migration nonprofit. In a folding chair, Maria Ramirez sifted by manila folders dated November 2023, when she’d arrived within the U.S.

Ramirez fled central Mexico, the place cartel violence claimed her youthful brother’s life, and requested Lopez Chavez how she might get well being care. Ramirez’s 4-year-old daughter – who pranced behind her mom, blowing bubbles and popping those that landed in her brown curls – has a lung situation.

Ramirez mentioned she would work wherever to maneuver from the lounge they sleep in, with only a blanket on the ground as cushioning.

In the places of work resembling a hostel’s well-loved communal area, Lopez Chavez cautioned Ramirez to seek the advice of a lawyer earlier than making use of for well being care. Sitting apart Ramirez had been two settled migrants providing assist and recommendation.

“A lot of stuff that you heard in Mexico (about the U.S.) was you couldn’t walk on the streets, you had to live in the shadows, you’d be targeted,” mentioned Ramirez. “It’s beautiful to come into a community that’s united.”

Lopez Chavez works with new migrants as a result of she remembers shackles snapping round her ankles after she was stopped for a visitors violation in 2012 and turned over to the U.S. immigration authorities.

“I just wanted to leave there because I’d never been in a cage before,” Lopez Chavez mentioned in an interview, her eyes filling with tears.

At her first court docket listening to, Lopez Chavez and her husband stood alone. At her second listening to, after Lopez Chavez was related to the neighborhood, she was flanked by new buddies. That wall of assist allowed her to maintain her chin up as she fought her immigration case earlier than being granted residency final 12 months.

Lopez Chavez now works to domesticate that energy throughout the neighborhood.

“I don’t want any more families to go through what we went through,” mentioned Lopez Chavez, who additionally encourages others to inform their tales. “Those examples give people the idea: If they can manage their case and win, maybe I can too.”

In Fort Morgan, practice tracks divide a cellular house park, the place many migrants reside, and town’s older properties. Some older migrants see new arrivals as getting higher therapy by the U.S. and really feel that’s unfair. The neighborhood can’t clear up each problem, and hasn’t laid the final brick on cultural bridges between the various communities.

But on the posada occasion, crowded within the One Morgan County places of work, the assurances of neighborhood itself confirmed by the eyes of partygoers as kids in cultural regalia danced conventional Mexican dances.

Among these bouncing across the lengthy room was 7-year-old Francisco Mateo Simon. He doesn’t keep in mind the journey to the U.S., however his mom, Magdalena, does.

She remembers how in poor health he turned as she carried him the final miles to the border. Now he spits out armadillo details between the nubs of incoming entrance tooth of their cellular house, then factors to his favourite decoration on their white, plastic Christmas tree.

“That’s our brand new tree,” mentioned his mom, as her eldest daughter practiced English with a youngsters’ ebook.

“It’s new,” she repeated, “It’s our first new tree because in the past we’ve only had trees from the thrift store.”

___

Bedayn is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit nationwide service program that locations journalists in native newsrooms to report on undercovered points.